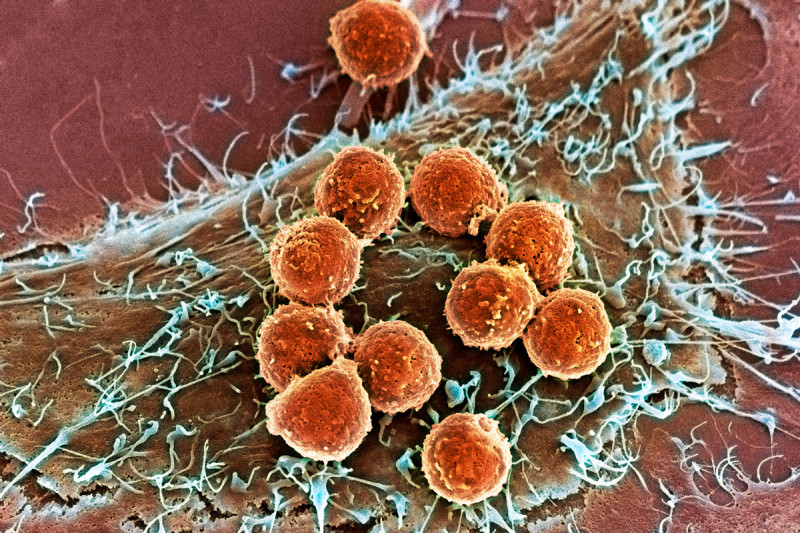

This image, captured by a scanning electron microscope, shows T cells (orange) attached to a tumor cell. Innovative treatments pioneered by Memorial Sloan Kettering researchers harness the ability of T cells to recognize and destroy cancer cells.

Each year, Science magazine announces one pivotal scientific achievement as the “Breakthrough of the Year.” Memorial Sloan Kettering researchers have played a leading role in pioneering this year’s winner: cancer immunotherapy.

“Immunotherapy marks an entirely different way of treating cancer — by targeting the immune system, not the tumor itself,” Science said in choosing this burgeoning field. Based on the idea that the immune system can be trained to attack tumors in the same way that it targets infectious agents, cancer immunotherapy exploits the ability to harness different types of immune cells circulating in the body.

A Rich History at Memorial Sloan Kettering

Although cancer immunotherapy is being touted as a recent breakthrough in cancer treatment, its origins at Memorial Sloan Kettering go back more than a century. In the 1890s, William Coley, a surgeon at New York Cancer Hospital (the predecessor to Memorial Sloan Kettering) discovered cancer patients who suffered from infections after surgery often fared better than those who did not. His finding led to the development of Coley’s toxins, a cocktail of inactive bacteria injected into tumors that occasionally resulted in complete remission. But eventually the use of this treatment fell out of favor.

In the 1960s, research by Memorial Sloan Kettering investigator Lloyd Old led to the discovery of antibody receptors on the surface of cancer cells, which enabled the development of the first cancer vaccines and led to the understanding of how certain white blood cells, known as T cells or T lymphocytes, can be trained to recognize cancer.

Back to topHelping Patients Today

One of the pivotal milestones cited in the Science article is the work of immunologist James Allison in identifying a protein receptor on the surface of T cells called CTLA-4, which puts the brakes on T cells and prevents them carrying out immune attacks. He later identified an antibody that blocks CTLA-4 and showed that turning off those brakes allows T cells to destroy cancer in mice. (Dr. Allison, who spent nearly a decade of his career at Memorial Sloan Kettering until last year, is now at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.)

Anti-CTLA-4 eventually became ipilimumab (YervoyTM), a drug approved in 2011 for the treatment of metastatic melanoma, the most deadly form of skin cancer. Dr. Allison, together with Memorial Sloan Kettering physician-scientist Jedd Wolchok, helped guide the development of ipilimumab from the first laboratory studies through the late-stage clinical trials that led to the drug’s approval.

Dr. Wolchok’s research on immune therapies for melanoma continues, including a study earlier this year that found that more than half of patients with advanced skin melanoma experienced tumor shrinkage of more than 80 percent when given the combination of ipilimumab and the antibody drug nivolumab, another promising immunotherapy drug under investigation, suggesting that these two drugs may work better together than on their own.

The other major area of research highlighted in the Science story is the development of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) therapy, based on the idea that a patient’s own immune cell type, called T cells, can be collected from blood, engineered to recognize cancer cells and acquire stronger antitumor properties, and reinfused to circulate through the bloodstream and attack those cancerous cells. Memorial Sloan Kettering has been a leading center in developing this technology.

The first successes in this field have come in the treatment of leukemia. In March, Memorial Sloan Kettering investigators reported that genetically modified T cells had been successful in rapidly inducing complete remissions in patients with relapsed B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), an aggressive form of blood cancer.

“This is a very exciting finding for patients with B cell ALL, directly borne out of our basic research on CARs for over a decade, and a landmark proof of concept in the field of targeted immunotherapy,” says Michel Sadelain, Director of Memorial Sloan Kettering’s Center for Cell Engineering, who led the study, along with medical oncologist Renier Brentjens.

Memorial Sloan Kettering continues to study this approach and now has clinical trials under way investigating it in other types of leukemia, lymphoma, and prostate cancer, with several more trials slated to begin soon.

Back to topLooking toward the Future

Today, investigators in Memorial Sloan Kettering’s Immunology Program in the Sloan Kettering Institute are conducting a diverse range of studies aimed at developing the next generation of immune-based cancer treatments.

For example, Immunology Program Chair Alexander Rudensky is focused on studying a subset of T lymphocytes called regulatory T cells, which are critical for keeping other white blood cells in check and therefore play an important role in controlling immune system reactions. Understanding how these cells function, and how to inhibit them will offer novel and effective ways to treat cancer.

The research also has implications for treating conditions characterized by an overactive immune system — including autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and diabetes.

Learn more about immunity science at Memorial Sloan Kettering.

Back to top