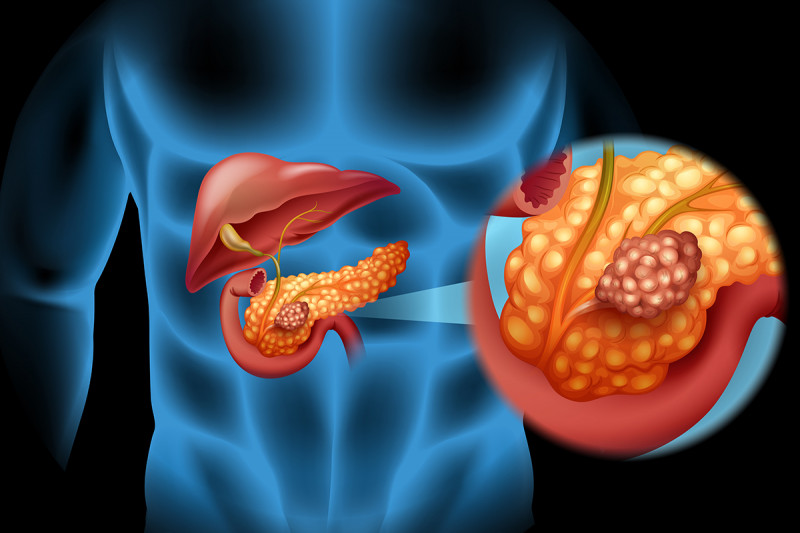

The pancreas is located at the intersection of major blood vessels, making surgery difficult.

Highlights

- Pancreatic cancer is not common but is very deadly.

- Standard cancer therapies are largely ineffective.

- New treatment approaches give reason for hope.

Pancreatic cancer is relatively rare but notoriously lethal. It is currently the third leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States — and it’s projected to move into the second slot by 2020.

The main reason is that pancreatic cancer has proven very difficult to treat compared with many other, more common types of cancer. Despite decades of research, the prospects remain bleak for those diagnosed, with a survival rate of 20% at one year and 6% at five years for all stages combined. Even patients diagnosed and treated at the earliest stage have a 50% chance that the disease will recur.

Below we discuss why this disease has foiled clinicians and researchers for so long and also explain why they have reason to hope that the outlook will soon be brighter.

Back to topPancreatic Cancer Is Rarely Caught at an Early Stage

MSK pancreatic cancer expert Steven Leach, director of the David M. Rubenstein Center for Pancreatic Cancer Research, explains that the disease usually does not cause symptoms in its early stages. Those that do occur — such as pain or weight loss — are often mistaken for signs of other illnesses. In addition, the pancreas is located in the back of the abdomen behind many other organs, making it hard for doctors to feel during routine examinations and even to conduct imaging tests to detect tumors.

“It’s not a frequently occurring cancer, so it becomes hard to generate cost-effective screening strategies for early detection, such as the use of mammography or MRI for breast cancer, or colonoscopy for colorectal cancer,” Dr. Leach says. “We have a long way to go when it comes to early diagnosis.”

Back to topSurgery Is Usually Not an Option

Pancreatic cancer is especially aggressive and its location makes it easy for it to spread into adjacent structures and organs such as the liver or stomach. It is usually diagnosed only after it has moved into surrounding tissue, if not other parts of the body. As a result, only about 15% of patients are good candidates for surgery.

“The pancreas sits in a tricky location, with major blood vessels, the bile duct, and the intestine all in the immediate neighborhood,” Dr. Leach explains. “When the tumor involves these major blood vessels, it generally can’t be removed.”

Even when surgery is an option, the procedure is very difficult and requires a great degree of expertise. “In high-volume centers like MSK, it’s become routine for the surgeons, who may do between 200 and 300 procedures a year, and we have good outcomes,” Dr. Leach says. “For many hospitals, whose doctors might do just ten a year, it is still a fairly high-risk operation.”

Back to topPancreatic Cancer Resists Drugs That Work in Other Cancers

Chemotherapies that are effective against other cancers don’t seem to work well against pancreatic cancer. Dr. Leach explains that one reason may be that pancreatic tumors are surrounded by a network of nonmalignant cells, called the stroma, which can act as a protective barrier.

“Sometimes as little as 10% of the whole tumor volume is occupied by the cancer cells, while the rest is made up of nonmalignant cells,” Dr. Leach says. In addition, the tumor usually contains a buildup of certain proteins, called matrix proteins, that cause blood vessels to collapse — which in turn prevents chemotherapy from reaching the cancer cells in sufficient amounts.

While some cancers have been successfully treated with targeted therapies, which block the products of specific genetic mutations, these drugs have not been developed for pancreatic cancer. Targeted therapies are effective in cancers that have a fairly large percentage of patients with the same cancer-causing mutation, such as EGFR in lung cancer, or BRAF in melanoma. Pancreatic cancer, by contrast, appears to be spread out over a large number of cancer-driving mutations, each involving a small percentage of patients.

“It’s more challenging to develop a drug that will be effective in only a small subset of patients,” Dr. Leach says. “It’s difficult to enroll enough people for a clinical trial, and there is less financial incentive for pharmaceutical companies.”

Immunotherapy, which has revolutionized treatment for many cancers, has also failed to have much effect against pancreatic cancer. Recent research has found that pancreatic tumors seem to evolve mechanisms that prevent the critical immune cells, called T cells, from infiltrating the tumor.

Back to topTurning the Tide

Despite these many hurdles, Dr. Leach says there is ample reason for optimism.

First, researchers now know more about who is more likely to develop pancreatic cancer. Patients who carry mutations in one of the BRCA genes — which have already been primarily linked to breast and ovarian cancers — are now known to be at higher risk for pancreatic cancer, as well as people who suddenly develop diabetes relatively late in life. These groups could be screened through endoscopic ultrasound, in which a gastroenterologist passes an endoscope into the intestine next to the pancreas to capture high-resolution images.

But something even simpler is needed to make screening more cost-effective, Dr. Leach asserts. MSK researchers are investigating liquid biopsies, which look for circulating tumor cells or tumor DNA in the blood. Analyzing this DNA for mutations could help detect pancreatic cancer at an early stage, and also provide critical information about the specific tumor type.

“There also is a lot of excitement about blood tests that measure large numbers of proteins that indicate pancreatic cancer when they are detected in certain patterns — what we call protein arrays,” he says.

In addition, MSK is making progress in developing new forms of imaging, led by radiochemist Jason Lewis and radiologist Richard Do, both to detect pancreatic cancer at an early stage and also to assess how it may be responding to treatment.

Perhaps the most promising development is a new initiative called Precision Promise, a large-scale clinical trial that will investigate multiple treatment options under one clinical trial design. Sponsored by the Pancreatic Cancer Action Network, Precision Promise is a collaboration among MSK and other leading institutions to use each patient’s unique molecular profile to determine the best treatment for that person. The trial will be conducted at 12 sites, including MSK. (Precision Promise will be discussed in more detail in an upcoming OnCancer story.)

“This is a really innovative initiative because we’re getting a wonderful partnership of leading academic centers with pharmaceutical companies that recognize its vast potential, and something they want to be part of,” Dr. Leach says. “It’s going to allow us to try things that simply weren’t possible before, and we’re excited to be able to participate in something that’s this important.”

Back to top